This pamphlet examines international cultural differences in the game of pool by investigating the bars and pubs of three representative countries: the United States, England, and Botswana. The senses of honor and ethics in these countries are analyzed in a comparative context, and judgements are made unflinchingly with regard to the moral superiority of particular national rules and customs. The author admits to being a United States citizen, but insists that every sincere effort has been made to belittle the customs of other nations fairly.

Honor is everything in the game of pool, particularly as played in bars and pubs, as opposed to the tournament game. "Was that the exact intended shot, did you really run four balls while I was in the bathroom, did you see me accidentally nudge that ball with my elbow while shooting," and so forth. Honor comes into play only when there is individual freedom in interpreting or admitting what has happened. In a tournament a referee is responsible for that--calling fouls, enforcing rules, declaring punishments. In other words, cheating is impossible. In a bar, on the other hand, all sorts of shenanigans are possible. There may or may not be any agreement about the rules, creating the distinct possibility of misunderstandings, ill feelings, deception, violence, and death. The problem is exacerbated for the international traveler, who may find that peculiar foreigners are playing some bastardized version of the real game.

In short, a sense of honor and ethics is indispensable where there are no referees. Honorable conduct, which is essential for the peaceful enjoyment of the game, can only be understood and practiced within the context of particular cultural norms. That's where this pamphlet comes in handy.

Let me emphasize once more that we are only concerned here with rules and customs as they are commonly practiced in bars and pubs, also known as "house rules." House rules can vary from bar to bar but certain rules are pretty consistent, and those are the ones we're dealing with here. These rules often have very little to do with the "official" rules, which are used in tournaments and are different in many respects. The official governing body for pool in the United States is the Billiards Congress of America (BCA); in England it's the English Pool Association (EPA). Many BCA and EPA rules are routinely flouted in bars and pubs, but research has shown that few friends are made in the course of pointing out the "real rules" during an average bar game. (However, it can still be fun if you're in the mood for it.)

A further note about official rules and governing associations: The EPA uses the so-called "World Eight Ball Pool Federation Rules," which, despite the use of the word "world," are suspiciously and completely English in character. Similarly, the BCA uses the "World Standardized Rules," which are as thoroughly American as watching TV all day. Thus we have two sets of "world" rules that contradict each other in countless ways large and small. Botswana already gains a bit of moral high ground here because it does not have a national association that tries to rule the world.

So, we will proceed by having a look at a series of key categories, comparing and contrasting the American, English, and Botswanian games, also noting the actual official rules just for fun, and we will make the tough calls regarding which system in each case is morally superior. Please note that we will not attempt to describe each and every rule, but only the ones where there are important distinctions between them that reveal differences in honor and morality. In this way we can gain a better understanding of international cultural relationships.

The first thing we must do, as in any relationship, is to have a look at the equipment.

First time American travelers to the UK might feel something like Gulliver when setting eyes upon the diminutive little tables and tiny little balls that they'll confront upon entering the pool playing environment. They might feel a sense of disorientation at the two-tone array of unnumbered solid red and yellow balls that surround the black eight-ball on the table. They might be tongue-tied when they find their lingo--their "stripes and solids," their "low and high," their "six in the corner"--has all been rendered meaningless.

Similarly, English travelers might feel like they will never muster the strength to move the huge and heavy American pool ball all the way across the vast expanse of green baize that seems to stretch out in front of them to the horizon.

English players will occasionally make jokes about the immense pockets on American tables, insinuating that the role of accuracy in the game has been compromised, and that sinking a shot in American pool is no more challenging than tossing a fish into the ocean. (In the traditional response, US players will make vaguely lurid references to having big balls.) In any case, the disproportionately small and narrow pockets of the English table are indeed notoriously unforgiving and do require a trainspotter's sense of precision.

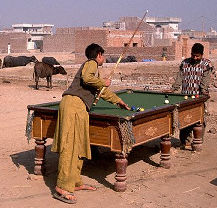

In Botswana the table and balls are English-sized, but the balls are numbered stripes and solids just like in the United States, making all visitors feel both at home and not at home at the same time.

Moral High Ground: England and Botswana. The equipment may be dinky and aesthetically displeasing, but those tiny hard little pockets do require somewhat greater accuracy, and that's the measure we're using.

How does one get onto the table in the first place, assuming it is occupied when you first walk in the door? Whoever wins the current game is the reigning champion, and gets to play again. Everyone else who wants to play is a challenger. There will normally be a list of challengers, a queue. You must find some way to join the list of challengers, which can range from zero to an infinite number of challengers on any given evening. A chalkboard name list is sometimes used for this purpose, but more commonly one uses the coin of the realm, by placing a representative coin on the edge of the table above the coin slots. This basic method applies universally in all our sample nations--the United States, England, and Botswana. However, there is an important difference in the English game.

In the United States, the tables take quarters; correspondingly, quarters are used as the placeholders at table's edge. In Botswana, the tables take one-pula or two-pula coins; thus these same pula coins are used at tableside when offering the challenge. In England, the tables usually take 50p coins, yet challengers avoid at all costs using actual 50p coins to hold their place. They will use any other sort of coin instead, for example a 2p coin. They'll have 50p coins, mind you, but they will keep them tucked away rather grabbily in their pockets, to be produced only at the last moment when it becomes necessary.

Why? Because if you put your 50p up there on the table, someone is liable to nick it for their game, leaving you with no 50p and no place in the queue. For this is the English custom, and it is the first honor-related concept the international traveler must master before entering the pub.

Moral High Ground: Tie between United States and Botswana. This "hide the 50p" business reeks of grabbiness.

|

Figure 2. English Pub Rack |

|

Figure 1. US Bar Rack |

In both the United States and England, it is the custom for the challenger to rack the balls and the reigning champion to break them. In Botswana, however, it is the reigning champion who racks, and the challenger who is invited to break. Other than that, they pretty much play the English-style game in Botswana.

It is usual in American bars to rack the balls so that stripes and solids alternate perfectly around the outside edge of the triangle (see Figure 1). The customary English rack has alternating diagonal lines of red and yellow balls except for a special swirly curly bit that keeps you on your toes (Figure 2). I note that in Botswana they are not as particular as all that about the rack so long as the eight-ball goes in its special place in the middle. An additional difference is that in the United States, the ball at the top of the triangle goes on the special marked spot, and in England and Botswana the eight-ball goes there.

Official Rules:

BCA: Eight-ball in the middle, a stripe in one back corner

and a solid in the other.

EPA: Eight-ball in the middle. Everything else is art.

Moral High Ground: Botswana. It's the only one of our sample countries that shows the incoming player (the challenger) any hospitality.

Let's say that a ball has been pocketed on the break. In fact let's say that a striped ball went down. Does the shooter automatically have to take stripes for the rest of the game? Yes, according to the most common custom in each of our sample countries. If both kinds go down, most people will say the shooter has a choice. However, many people also play that the table is always open after the break, regardless of what goes down. This "always open after the break" rule is slightly more common in the United States than in England or Botswana.

Official Rules:

BCA: Always open after the break, staying open until the first

successful called shot.

EPA: Open after the break, but before taking the next shot

the shooter has to say "I'm going for the yellow ones"

or "I'm going for the red ones," and then even if

he misses the shot he's still stuck with that color. Strange,

eh? But true.

Moral High Ground: Since all the countries use the same system for the most part, at least in bars and pubs, let's call it a draw. However, just for fun, it should be noted that the BCA/EPA "always open after the break" rule is morally more rigorous than the customary "take whatever goes down" because its provides greater individual freedom and is based on skill rather than luck. It also potentially brings a certain degree of honor into play. Suppose for example that you sink a stripe on the break but you decide to go after solids anyway. Maybe you like the way all the solids seem to be laid out in front of the holes more conveniently. Well, even though your decision is based on self-interest, at least it also concedes one ball to the opponent. Very gracious. It is also somehow less grabby than going out of your way to get more stripes.

The question soon arises, "What constitutes a foul?" Here is where we really get into the role of honor in the game of pool. Everyone will agree that it is a foul (or "scratch") when the cue ball ends up in one of the pockets, or when a ball goes flying off the table completely. Beyond that, we are in a shadow zone of competing theories and conflicting assumptions. Each country has a bit of a funny mix of strictness and laxity, making an overall judgement as to moral superiority very difficult indeed. But we will not flinch.

Before we analyze what constitutes a crime, let's first describe the systems of punishment. It will make things easier for us later on. Trust me. I've revised this section many times, trying to make it as simple and clear as possible.

There are two drastic differences between the English/Botswanian game and the US game. The first major difference is that you have to call your shots in the United States, and you do not have to call your shots in England and Botswana. In England and Botswana, slop counts. The second major difference is the respective systems of punishment for fouling. The following revelation will shock any ordinary American, but in England and Botswana the opponent gets two turns in a row after a foul. You heard me right: You make a foul, then its their turn to shoot, and they go until they miss, and then they get to keep going! This peculiarity is of course unheard of in the American game.

OK. Just hold onto that information for a moment; it will be important later in our story. Let us now turn our attention to some examples of fouling in pool. There are basically two different kinds of fouls: fouls where the cue ball goes into one of the pockets and fouls where the cue ball does not go into one of the pockets. First let's look at what happens in the case of the clearest and most obvious type of foul: the type where the cue ball goes into one of the pockets.

|

Figure 3. The Kitchen |

On one point we have universal agreement. Whether you are in a bar in Botswana, England, or the United States, the cue ball has to come back out of that pocket before the game can continue. Naturally you have to put the cue ball back onto the table somewhere. Where do you put it? All our countries agree: You put the cue ball in the kitchen. What is the kitchen? The kitchen is that end of the table you broke from, as seen in Figure 3.

Parenthetically: I lied. Not everybody says the cue ball has to go into the kitchen. Sometimes in US bars the "ball in hand" rule is used after a foul. The "ball in hand" rule says you can put the cue ball anywhere on the table you like. The "ball in hand" rule also happens to be the official BCA rule. In bars it is used very rarely, but it is not unheard of, so I must mention it to be thorough. The "ball in hand" rule is never used in England or Botswana. In England and Botswana they have never even heard of the "ball in hand" rule. Now let's return to our example.

In both England and the United States, when playing the cue ball from the kitchen, it is most commonly observed that the shooter must shoot at an object ball that is outside of the kitchen. If the only available object ball happens also to be in the kitchen, then the shooter is forced to try one of those difficult bounce-off-the-rail-and-back shots. In Botswana, however, there are no qualms about shooting at object balls within the kitchen. Botswanians are very happy to shoot at a ball in the kitchen without the least sense of shame whatsoever. Many English people would be surprised to hear it, but the Botswanian method happens to reflect the official EPA rule.

OK. Thus far, with a couple of minor discrepancies as noted, there is relative harmony in the pool universe. When the cue ball goes in the pocket, you put it in the kitchen. In the United States, that's the end of the story; the game continues normally. In England and Botswana, as mentioned above, the shooter is also awarded an extra turn. Fine. We are not troubled by anything terribly complicated so far. All is clear.

Now let us examine the other kind of foul--the kind where the cue ball does not go into one of the pockets. What sort of foul could that be? Good question. Well, one of the basic rules of eight-ball is that the first ball you hit with the cue ball is supposed to be your own ball. You're not allowed to hit your opponent's ball first, you're not allowed to hit the eight-ball first, and you're not allowed to hit nothing at all. You have to hit something, and the first thing you have to hit is your own ball. And if you don't do that, you have committed a foul.

So let's say you take your shot, and your shot isn't very good. You fail to hit your ball. The cue ball takes a little roll around the table without disturbing any of the balls on the table at all. If you are in a bar in the United States, the only thing that happens is your turn ends. That's not really a punishment, because your turn ends anyway, because you didn't sink a ball. But nobody in the bar can think of anything to do to punish you. The cue ball has not gone into a hole. It can't be taken and put into the kitchen. So what on earth else can they do to you? Nothing. They know it's some kind of foul but there is nothing they can think of to do to you. So, everyone may feel vaguely dissatisfied and suspicious, but still no punishment actually happens. They just can't think of anything. (According to the official BCA rules, incidentally, there is a remedy: "ball in hand," like on any other foul.)

Contrarily, in England and Botswana, they know exactly what to do, and they do it: They give your opponent that extra turn. This extra clarity can be considered an advantage of the extra turn system.

So far, all our sample countries will agree that all our sample fouls are fouls. They will all agree that the cue ball in the hole is a foul. They will all agree that if you don't hit your own ball first it's a foul (only in US bars they don't know what to do about it). Now let's look at a different sort of situation, one that is a foul in England and Botswana, but that is most certainly not a foul in the United States. I'm talking about when you accidentally sink one of your opponent's balls.

Now, remember that in England and Botswana, slop counts. In other words, accidents that favor the shooter are A-OK. Yet in this very same system, if you sink one of your opponent's balls accidentally, you're finished, even if you also sank one of your own. And not only do you have to stop shooting, your opponent gets two turns in a row. The inherent punishment of having sunk your opponent's ball is not considered sufficient. Additional punishment is heaped on. This can be interpreted as a very strict standard of honor, although you must admit it looks slightly funny sitting there next to its loosey-goosey brother the "slop counts" rule.

In American pool, if you accidentally sink an opponent's ball while you also successfully pocket your own, it's no problem. Sure, you regret it, it's not great, but it's nothing more than a little gift that you give to your opponent. It doesn't end your turn. Life goes on. You keep shooting.

While it must be conceded that the American willingness to overlook this particular form of unintended result can be considered a kind of sloppiness in its own right, overall the level of moral rigor is undoubtedly higher in the United States than in either England or Botswana. In most bars it is not only necessary to call the ball and the hole, but the exact path the balls will take along the way, i.e., every kiss and carom involved. In fact if you call the six in the corner off the fourteen and then instead the six goes in perfectly clean, honor dictates that you abdicate the table at once, leaving a trail of gleaming chivalry in your wake.

Moral High Ground: United States. Allow me a brief explanation. With apologies to my outraged friends in England and Botswana, this two-shot business is crap. Two turns in a row? Being allowed to miss and still continue? Being allowed to do what your opponent has just been punished for? Two wrongs making a right? No. One cannot proceed this way and feel honorable. On the contrary it fosters a secretly shameful feeling, a dirty feeling. It is morally unacceptable.

Each of our sample countries presents us with a puzzling mixture of sloth and rigor, honor and grabbiness. It must be noted that honor in pool is ultimately a personal matter that resides in individual conduct and manner, rather than being neatly divisible along national lines. Beyond the shared assumptions about rules and customs, very often in practice it is the individual traits that set the tone of the game and establish claims to the moral high ground. For example, if in preparing to shoot a player just barely nudges a ball accidentally with his bridge hand or miscues ever so slightly, it is not always seemly to play by the actual rules no matter how clear and customary they may be. What instead should happen, honor-wise, is that the offending player should stoically and sincerely volunteer to yield the table and accept whatever other punishments may be coming his way, and the opponent should brush aside his offer in a warm and generous manner, urging him to continue and insisting that such unforgiving interpretations have no place in a friendly game. Thus, ultimately honor transcends both rules and nationalities and can perhaps never be precisely defined.

However, this truth cannot be used as a cheap excuse to avoid making a final determination about which country has achieved overall moral superiority. Let us now turn unflinchingly to the bottom line.

Overall Moral High Ground: Botswana, of course. Colonization! Imperialism! Oppression!