The sausage figures prominently in 19th century literature and was present at the birth of the existential novel. Pig and pork references color the writing of Dickens, Hamsun, Sartre, Camus, Bulgakov, and Dostoevsky, shattering the comfy world of the self-satisfied bourgeois and replacing it with something more, well, sausagey. These authors look beyond the taut and regular skin of urban existence to an offaly underside that is ready to burst through the seams at the slightest provocation. They are tormented by the city, yet they cling to it like men possessed. Hopped up on coffee and cigarettes, they crave a good meal. What better vehicle than the sausage to convey their fevered dreams and nightmares?

Dickens, in Great Expectations, serves up his sausages in the suburbs, but the city is never far off. Pip, the eager young protagonist, visits the fortified home of that perfect bureaucrat, John Wemmick, who excels at keeping his home life absolutely separate from his job as a dodgy solicitor's clerk in the greasy heart of London. Wemmick assures Pip that "the office is one thing and private life is another. When I go into the office, I leave the Castle behind me, and when I come into the Castle, I leave the office behind me." (208) At home Wemmick has set up his own version of The Good Life, including a vegetable garden and a pig that, according to Pip, "might have been farther off." (209) The same pig is turned into sausages not long afterwards and Pip is invited to have a nibble:

"You look very much worried, and it would do you good to have a perfectly quiet day with the Aged -- he'll be up presently -- and a little bit of -- you remember the pig?"

"Of course, said I."

"Well; and a little bit of him. That sausage you toasted was his, and he was in all respects a first rater. Do try him, if it is only for old acquaintance sake."(373)

Wemmick's homemade sausages remind us comfortingly of his artisanal private life, successfully shielded from the soullessness of the big city. But the unnerving demise of the pig also evokes Wemmick's blood-chilling occupation in the heart of London, where he is employed chiefly in securing the "portable property" of condemned men for himself and his employer Mr. Jaggers. Unsurprisingly, Jaggers' law office is located slap bang in the center of the Smithfield slaughterhouse district where, as Pip notes, the streets are "all asmear with filth and fat and blood and foam." (165)

Not content with suburban sausages, Knut Hamsun jumps right to the urban butcher's shop where bangers of an unhealthful shade of pink push themselves on the fevered imagination of the main character -- a young, highly strung man who is voluntarily starving himself on the streets of Christiania (the old name for Oslo), for no particular reason. He sustains himself by writing delirious articles for the local newspaper for which the kindly editor occasionally tosses him a few Kroner, and is gaily on his way to the park to begin writing his masterpiece on Crimes of the Future when he meets with the sausages:

In front of a butcher's shop there was a woman with a basket on her arm, debating about some sausage for dinner; as I went past, she looked up at me. She had only a single tooth in the lower jaw. In the nervous and excitable state I was in, her face made an instant and revolting impression on me -- the long yellow tooth looked like a finger sticking out of her jaw, and as she turned toward me, her eyes were still full of sausage. (7)

Having glimpsed the gaping horrors and suffocating routine that lies beneath the cosy familiarity of the high street, our young man is quite thrown off his game and accidentally pawns his only pencil, sabotaging another day's work. Christiania, "that strange city no one escapes from until it has left its mark on him," (3) torments and exhilarates the hero of Hunger and it is only by escaping its confines on a cargo ship that he regains his sense of proportion.

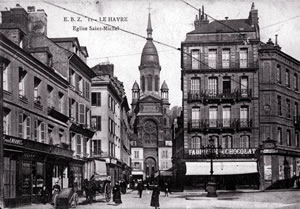

A similar fate awaits Sartre's hero, Antoine Roquentin, a historian who is holed up in the stuffy town of Bouville (based on Le Havre) writing a biography of long-dead local dignitary, the Marquis de Rollebon. Out and about for the Sunday promenade, Roquentin's gaze is drawn to one of the townsmen outside the butcher's window:

Standing against the window of Julien, the pork butcher's shop, the young designer who has just done his hair, still pink, his eyes lowered, an obstinate look on his face, has all the appearance of a voluptuary. This is undoubtedly the first Sunday he has dared cross the Rue Tournebride. He looks like a lad who has been to his First Communion. He has crossed his hands behind his back and turned his face towards the window with an air of exciting modesty; without appearing to see, he looks at four small sausages shining in gelatine, spread out on a bed of parsley. (46)

The sausages are just the start of it. Roquentin, beset by dissolving, palpitating chestnut trees and visions of pimples that split open to reveal laughing eyeballs, soon finds he can't write another word about M. de Rollebon and is completely suffocated by Bouville, which has something distinctly sausagey about it.

I am afraid of cities. But you mustn't leave them. If you go too far you come up against the vegetation belt. Vegetation has crawled for miles towards the cities. It is waiting. ...They let plants grow between the gratings. Castrated, domesticated, so fat they are harmless. They have enormous, whitish leaves which hang like ears. When you touch them it feels like cartilage, everything is fat and white in Bouville because of all the water that falls from the sky. I am going back to Bouville. How horrible!

Before long he packs up and runs screaming for the brighter, steelier city of Paris, where we hope for but don't expect him to find contentment.

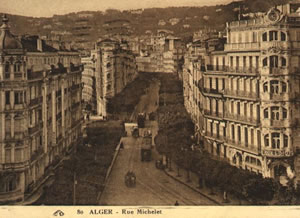

Like Sartre's hero, Camus' Meursault is relieved to get back to his city of Algiers, yet seems maddeningly hemmed in by it. The white flesh in the red earth dug up for his mother's funeral outside the city is reminiscent of the cartilage in Sartre's account of Bouville:

Then there was the church and the villagers on the sidewalks, the red geraniums on the graves in the cemetery, Perez fainting (he crumpled like a rag doll), the blood red earth spilling over Maman's casket, the white flesh of the roots mixed in with it, more people, voices, the village, waiting in front of a cafe, the incessant drone of the motor, and my joy when the bus entered the nest that was Algiers and I knew that I was going to go to bed and sleep for twelve hours.

Throw in a sausage and the reader's sense of security in this urban nest is immediately shaken, replaced by an air of foreboding. To be extra sure, in L'Etranger Camus makes his a blood sausage. Meursault the impossibly low-key bureaucrat is invited round to the thuggish Raymond's house for some blood sausage and wine:

We went upstairs and I was about to leave him when he said, 'I've got some blood sausage and some wine at my place. How about joining me?' I figured it would save me the trouble of having to cook for myself, so I accepted. He has only one room too, and a little kitchen with no window. Over his bed he has a pink-and-white plaster angel, some pictures of famous athletes, and two or three photographs of naked women.

Before long, Meursault is in deep with Raymond and murdering an Arab on the beach in the midday sun.

By all of these accounts, the sausage has an unsettling effect, especially on the jangled nerves of the sensitive young man about town. Pink and boastful, cheerfully overfed and sure of itself, its underside neatly concealed beneath the taut regularity and neat twists of its surface, the sausage captures the artificial splendour of the bourgeois city. Crammed with offal, ready to burst, adulterated with sawdust, the sausage has a cheeky existence that seems ready to overflow its boundaries and reveal sinister underpinnings and hypocrisies. Poised ready to overflow the neat and orderly existence bestowed upon it by the sausage machine it points beyond the orderly flowerpots of the town square toward something chaotic, intestinal, and dark.

The handsome megalomaniac Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, wakes up after a troubled sleep and the first thing he wants is sausage:

'Here, Nastasya, please take this,' he said, feeling in his pocket (he had slept in his clothes) and pulling out a handful of copper coins, 'and go and buy me a roll. And a bit of sausage, too, whatever's cheapest, at the pork butcher's.' (29)

The housemaid, Nastasya, talks him into some cabbage soup instead but, regardless, he is soon out killing the old moneylender and her halfwit daughter Lizaveta in cold blood. Admittedly the sausage connection is here tenuous at best, but the grip of the Petersburg summer on Raskolnikov's sensitive young mind captures well the sense of suffocation of the highly strung young man in the city:

It was terribly hot out, and moreover it was close, crowded; lime, scaffolding, bricks, dust everywhere, and that special summer stench known so well to every Petersburger who cannot afford to rent a summer house -- all at once these things unpleasantly shook the young man's already overwrought nerves. (4)

Pip, Roquentin, Meursault, Hamsun's nameless hero, and Raskolnikov all feel the city pressing on them and intensifying their highly strung natures. And all of them, with the possible exception of Raskolnikov, have unsettling encounters with sausage. Leaving the city for the countryside provides only temporary solace, and the rural is invariably a hinterland that is quickly unsatisfying or plain disturbing. Only the taut sausage skin of the urban environment can keep this untamed and oozing void in its place, albeit on a superficial level that our protagonists quickly penetrate, getting themselves into all manner of trouble.

In Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, events take a Satanic turn in the guise of a gentleman-magician by the name of Woland who wreaks havoc on Moscow. Woland, who turns out to be the devil himself, pays a visit to the home of the extremely hungover theatre manager Stepa Likhoyedev and invites him to dine on small pan of sausages before casting a spell that transports him instantaneously to the seaside resort of Yalta, fifteen hundred kilometers away.

'I cannot,' put in the new arrival, 'understand how he ever came to be manager' --his voice grew more and more nasal--he's as much a manager as I am a bishop.'

'You don't look much like a bishop, Azazello,' remarked the cat, piling sausages on his plate.

'That's what I mean,' snarled the man with red hair and turning to Woland he added in a voice of respect: 'Will you permit us, messire, to kick him out of Moscow?'

Like the others, Bulgakov points to something gone wrong beneath the surface of the city, a chaos bordering on madness that has crept ominously into the daily life of the capital, threatening to erupt at any moment, especially if helped along by Woland's trickery.

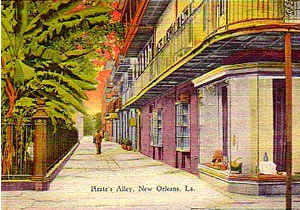

Finally, it remains to mention the hot dog as a particularly adulterated form of the sausage that has crept into more recent literature, underscoring the idea that we are on a road to hell of one sort or another. In A Confederacy of Dunces, Ignatius J. Reilly's stint as a Rabelaisian hot dog salesman is just one of his many bullseye attempts to turn his hometown of New Orleans upside down, exposing its more farcical elements along the way. Arriving at the hot dog magnate's headquarters, Ignatius ventures to sample the wares:

'May I select my own?' Ignatius asked, peering down over the top of the pot. In the boiling water the frankfurters swished and lashed like artificially colored and magnified paramecia. Ignatius filled his lungs with the pungent, sour aroma. 'I shall pretend that I am in a smart restaurant and that this is the lobster pond.'

While bent on its destruction, Ignatius is at one with his city and recalls his one attempt to leave it with unmitigated horror:

'Leaving New Orleans also frightened me considerably. Outside of the city limits the heart of darkness, the true wasteland begins.'

As Ignatius reminds us, aside from all this yawning chaos there is something very tasty and comforting about the sausage. In the sausage imagery there is an attraction to the civilized stomach gurgles of the bourgeois dining in his comfortable city dwelling or cafe. So what, really, is the role of the sausage in these diverse novels? Is it put there on purpose or are the authors just hungry? Some of them, it is certain, existed on coffee and cigarettes, and could have done with a good meal to settle their nerves. After all, you do not write a novel like Hunger on a full stomach. Hamsun, who purportedly cured himself of consumption by riding on the top of a train from Oslo to Bergen taking in large gulps of air, was literally starving in Oslo in 1879-80 and in 1886, the period of his life from which many of the experiences in the book are drawn.

While the sausages in the butcher's shop window are disturbing, they also suggest something eminently desirable. When the hero says goodbye to Christiania, "where the windows of the homes all shone with such brightness," he is already feeling nostalgic. The sense of horror is gone and the city is safe and warm without being dangerously mundane or shallow. While these writers bring into sharp focus the hypocrisies of modern living, the gnawing meaninglessness of existence, their angst, one feels, is nothing that a nice girlfriend and a home-cooked meal wouldn't cure. While the sausage imagery presents an immanent critique of the self-satisfied and the superficial, it also talks back to the author, counseling, "eat me, and everything will be OK." Makes you want to put down your espresso and order some bangers and mash. It really does.