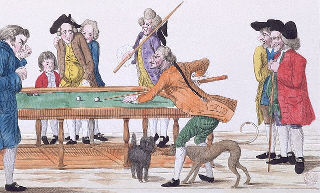

Please note: The Billiards Congress of America (BCA) does not endorse smoking, drinking, or brawling during the game of pocket billiards.

About the rules that govern the game of pocket billiards, two points need to be made clear at the outset:

The rules as explained here are a combination of official world standardized rules, common house rules, and rules that we have made up based on years of experience and advantage-seeking. With this pamphlet in your back pocket and a willingness to hurl things and flee, you can face any opponent with a devious confidence. See also Your Inner Pool Shark, Part One: The Mental Game for a further explication of how to control the psychological dimensions of pocket billiards.

Certain basic official rules are common to all games of pocket billiards. These official rules are important to know, because a few of them are not widely acknowledged and can therefore be used very effectively to stun the average bar player at critical moments. Also, the only way confidently to reject the preposterous ideas with which one is occasionally confronted is to have a good and thorough knowledge of the official rules of the game, which are known as the World Standardized Rules for Pocket Billiards. These can be obtained in their entirety from several sources, not least of which is the Billiards Congress of America. Here we'll just cover the most important official rules and their "house rule" variations, and we'll offer our recommendations on the best way to play the game.

Footwear

The first thing you have to know about playing any game of pocket billiards is that you have to have normal shoes on. This is not a joke. It's a real rule, the twelfth of the general rules of pocket billiards: "Foot attire must be normal in regard to size, shape, and manner in which it is worn." We strongly advise you to examine your opponents' footwear before you consent to engage in a game with them. A critical frown at the footwear followed by a firm citation of Rule 12 is one of the best ways to get your opponent off balance right from the start.

Acts of God

It is unlikely that you will witness an Act of God during the game of pocket billiards, or see balls moving by themselves. However, it is not entirely unlikely that a) your opponent will claim that such things have happened when in fact he has reorganized the table while you were in the bathroom; or b) you will do the same thing to your opponent, which may be advantageous under certain conditions.

Therefore it is good to be aware that the official BCA rules cover these kinds of eventualities. For Acts of God, lighting fixture failures, limited nuclear war, or anything else that results in non-player movement of the balls on the table, simply respot the balls as near as possible to their original positions. If the balls move "by themselves," however, the rules call for respecting their chosen positions. The only exception is if they go into a hole more than five seconds after being shot, in which case they are to be carefully removed and respotted.

It is clear that these special rules can be exploited to good advantage so long as you can keep a deadly earnest expression on your face as you explain them to your opponent. Say for example one of your balls is in a particularly terrible position on the table, and your opponent's attention is diverted for a moment by a trip to the bar or the bathroom. Such scenarios represent excellent opportunities to take the ball in hand and place it in a more expedient position. If, upon the opponent's return, you are questioned, you can say the ball moved by itself and must, according to the official rules, remain where it now lays. The counter to this gambit, should it happen to you in reverse, is to argue that some force, such as an Act of God, must have acted upon the balls, necessitating a respotting.

|

Nineball: An Addendum OK. The authors have come under heavy fire for giving short shrift to the serious game of nine-ball. We wanted no part of it, but unfortunately we were in a position of respecting a couple of the key people who were trying to convince us. So we listened, and we agreed to try it. We learned a little bit more about the rules, and there is actually one rule that is very nice: Slop counts. You don't need to call your shots. All you really need to do is hit the lowest numbered remaining object ball first, and whatever happens to go in, hoo hah, whoopee, magic. It almost feels dishonest. It's nice. Other than that, we still maintain it's a waste of six good balls. |

Let us now turn our attention to some of the particulars about the game itself. Most people play eight-ball. It's true that many people play nine-ball as well, and it's probably a cooler game all in all, mainly because most people don't play it, but there are two problems with nine-ball.

First, we don't know how to play it. Second, it seems such a waste to use only nine balls, particularly if you're playing on a coin-operated table and you've paid for fifteen balls. So that's enough about nine-ball. There are other games too but we don't know what they are. So let's talk about eight-ball. Eight-ball is the main game.

There are lots of rules in eight-ball, and different schools of thought. The World Standardized Rules, accepted by all the proper authories, govern all your major tournaments. They are very clear and very thorough and very strict.

House rules are a bit slipperier. Nominally they are the rules held by the particular "house" in which you are playing pool, except that it can also mean any rule, no matter how eccentric, that the person you're playing happens to believe is true. Some house rules are so common, however, that there is a misperception that they are actually the official rules. Let's have a look at a few of the differences here, along with our recommendations.

Here is an area where the most common house rule is a pile of crap. Most people think they have to alternate solids and stripes along the outside edge of the triangle. In fact, if they do it this way, they violate the official rule, which is simple, beautiful, and better. The official rule requires only that the eight-ball goes in the middle, and that there is one stripe and one solid occupying the two back corners of the triangle. It doesn't really matter too much how they get set up though, so we do not advise making a big issue of it if somebody screws up. We do of course advise snorting subtly yet condescendingly when you notice somebody setting them up in the common, ignorant manner described above. The point is to elicit a "what?" from the opponent, and then to deliver an "oh, nothing." It cannot be underestimated how exquisite it is to feel secretly superior to your opponent in ways that only you understand.

[zoom] Figure 1. The Perfect Rack |

We happen to know the best and most elegant way of setting up the rack. It is an optional enhancement, mind you, but it satisfies the requirements of the official rule as well as achieving a higher aesthetic. Please refer to Figure 1. Notice how the diagonals comprise lines of stripes and solids, except for the right-most diagonal, whose lower stripe is nestled in a graceful curve of solid balls. It embodies a Japanese ideal of asymmetry in a quintessentially English fashion, and may well annoy your opponent in an American pool hall. [Note: The rack shown in Figure 1 is a special case of The Perfect Rack, known as The Even More Perfect Rack, or The Schaffer-Peterson Variation, named in honor of the half-mad gypsy scholars Marc Peterson and Drew Schaffer. In addition to adhering to all our little above-mentioned rules, the Schaffer-Peterson Variation keeps the solid-stripe color pairs together and follows the rainbow color order in a sort of clockwise fashion. An inspired work of subtlety and rare genius.]

A common house rule is that whatever sort of ball goes down on the break is then what the breaker must continue to shoot, and if both a stripe and a solid go down, it's either a choice or whatever type went down first (depending on whose house rule we're talking about). Here we strongly endorse the official rule, which is also not uncommon in bars: the table is always open after the break. The determination of stripes or solids is based on the first legal, intended shot. If you sink a stripe on the break and then choose to shoot solids, and your opponent objects, snort condescendingly and say "actually, it's always open after the break" with a tone that clearly implies an appended "you moron"; be prepared to grab a barstool or a bottle to strengthen your argument.

Another interesting, little-known quirk of the open table is that you can legally shoot a "mixed combination," i.e., hit a stripe first to sink a solid, or vice versa. Here we advise informing the opponent in advance of your intention, because he is a) unlikely to object, since it isn't a very big deal, and b) he may be made to feel subtly inferior in the ways of the game.

In both the official rules and most house rules, you have to call your shots in eight-ball. Still, it inevitably occurs that you're faced with some novice opponent in a bar who is baffled and/or appalled by this concept. You are then faced with a choice. One alternative is to appear gruff and inflexible as you insist on the rule as a matter of principle. Then you get to watch the joy and enthusiasm drain from their freshly washed faces as they come to terms with the reality that they are about to waste their quarters and approximately 15 minutes of their lives on a tense encounter with an anal-retentive beer-swilling gasbag. That sort of scene can put a man off his mood for hours and is best avoided. It is ultimately far better to say "oh, it doesn't really matter" while hoping to have a chance at some point during the game to sink a difficult bank shot and then hand the table over to them, saying "no no, I didn't call the kiss off the nine. I know we're not calling shots but I just can't let myself get away with that one. You go on ahead."

As a matter of plain fact, according to the World Standardized Rules for Eight-Ball it is not actually necessary to call each kiss and carom that your object ball might take on its way to the hole. This rule presented your authors with something of a dilemma, inasmuch as we spent years making a painful and begrudging transition from great laxity into our present condition in which we have meticulously cultivated senses of honor.

Originally, we didn't like calling any shots, feeling that if Lady Luck decided to smile upon us it would be arrogant of us to snub her kindness. As we improved in skill, we saw the beauty of called shots, and maintained the highest ethical standards in that department; every carom, every kiss had to be intended or the shot had failed. We then found that we had exceeded the requirements of the World Standardized Rules, had in effect made the world a little bit more of an unrelenting and hard place.

Failure to call the kiss in many pool halls today is likely to elicit the sort of condescending reaction described, and indeed advocated, above. More importantly, I'm afraid we must say here that once the mental bridge has been crossed to a level of more strictly described intention, there is no going back to a more languorous state without feeling undeniably feeble. On the other hand, is one to deny oneself a potential advantage in a game when the rules are actually favorable? What is one to do?

The answer lies in an understanding of the context. When ostentatious honor may undermine the opponent's serenity, by all means employ it, even if it requires a short-term sacrifice. But don't be shy about adopting a reverse holier-than-thou approach when necessary, such as by saying "ahh, yes, I was once like you, calling every kiss; then I read the actual rules."

Finally, there also remains the subtle phenomenon of the "unspoken" call. While all shots have to be "called," this requirement does not mean that in fact you need to say out loud what your plan is before every shot; obvious shots can be left unspoken. In practice, this "gentlemen's agreement" can be abused and exploited to good effect (see below under "Table Scratches").

Figure

2. The Kitchen Figure

2. The Kitchen |

In cases where the cue ball gets sunk, the official rule is "ball in hand," which means you can take the cue ball and put it anywhere you like on the table, regardless of how much it feels like cheating. The more common practice is the house rule, whereby the cue ball goes behind the "head string," also known as the "kitchen" (see Figure 2). From there you have to shoot out of the kitchen, even if all your balls are in the kitchen and it means you have to do an impossible bank shot off the far cushion. Both methods have merit.

Ball in hand is a good way of ensuring that nobody screws up on purpose just to stick it to the other player. For example, if all your balls happen to be in the kitchen, and we're using the "cue ball in the kitchen" rule, and I don't have a very good shot, I might be tempted to scratch just so you'll have to take one of those ridiculous over and back shots. In this circumstance, putting the ball in the kitchen actually gives an advantage to the person who presumably ought to be punished, i.e., the one who fouled.

However, ball in hand seems too easy, and may create the unreasonable expectation that you will proceed to run the table. Moreover, the house rule is so common that insisting on "ball in hand" may be more trouble than it's worth, although it may be a fine way to incite a barroom brawl, as appropriate.

Take the ball in hand if you're in a jovial mood, that's our advice. If questioned, laugh in bashful mock apology for assuming that the opponent played by the "real" rules. Be flagrantly gracious about consenting to play from the kitchen. Then, if later in the game the opponent appears to scratch on purpose just to put the screws to you, we advise soaking him with a pint of lager, preferably not your own, and making your way hastily to the nearest exit.

Here's where things get tricky. Table scratches are when you make an illegal shot but the cue ball remains on the table. Table scratches can include sinking your shot in an unintended way, e.g., sinking a shot in an unintended pocket, hitting the opponent's ball with the cue ball first, or missing everything entirely. In your average bar game, the most common house rule on a table scratch is that you yield the table, letting the cue ball remain wherever it came to rest. The official rule on any kind of scratch, table or otherwise, is clear and strict: ball in hand.

In a rule that we feel may be an original contribution to the game, we advocate a system of "prerogative" to govern this situation. In the "Table Scratch Option" the offending player calls "table scratch option," meaning the incoming player has the option of letting the cue ball stay where it is or moving it to the kitchen (or taking ball in hand). This approach clearly puts the pressure on the opponent, since he must either take the high road, foregoing the advantage, or feel slightly guilty for grabbing the cue ball, which can disturb his serenity and affect his game. There is at least one other player in the world who uses this rule as we do, but he has disappeared into New Orleans, apparently leaving behind an unpaid utilities bill and an angry roommate, but that's another story best left for another time.

It may be worth noting in this context some of the subtleties involved in certain table scratch situations. We are thinking here of the shot that gets sunk in an unintended fashion but that may nevertheless hold the possibility of appearing to have been sunk in an intended fashion. For example, you call "combination" but the wrong ball goes in, or your "obvious" uncalled shot goes in a surprise hole. In such cases, it may be best not even to look up before continuing on with your next shot. Keep your head down, your face straight, and proceed as quickly as possible.

However, some people prefer to employ ostentatious honor and say "no, no, that wasn't the combination I had in mind," or some such in an effort either to establish a moral high ground or to confuse and intimidate the opponent. Your authors, when playing each other, are doggedly honorable in these matters, mainly because we can easily tell if each other are lying.

Many people play that if you sink the eight-ball on the break, you automatically win, in contrast to the usual logic. According to the official rules, it is neither a win nor a loss. The breaker can ask to have the balls racked again and start over, or can have the eight-ball placed back on the table and continue shooting. If the cue ball also goes in, the incoming player has the same options, but must in either case put the cue ball behind the head string.

This, again, is a bit tricky. We must note that on coin-operated tables, the actual rules are impossible unless you want to spend more quarters. This fact of life is probably responsible for the evolution of the "automatic win" house rule. That rule is completely arbitrary, of course, as it would make just as much sense to call it an automatic loss. No; it would make more sense, because it would be consistent with the main rule that if you knock the eight-ball in before sinking all of your balls, you lose. Why some special case rule to turn an ordinary blunder into a miraculous victory? This automatic win business was no doubt instigated by someone who committed the offense and was persuasive or frightening enough to convince everyone else not to argue.

A third option would be to nominate another ball to be a replacement for the eight-ball. This rule makes good sense on coin-operated tables because it gets you more game for your money; instead of one shot, game's over, all those balls wasted, it's oops, let's make the best of it. The nominated ball should be one of the ones belonging to the non-breaker, since otherwise it would confer an advantage on the person who should be punished.

Anyway, if you sink the eight-ball on the break and someone comes over to shake your hand, we advise you to keep quiet and act gracious. If your opponent sinks the eight-ball on the break, we advise you to console him politely. If he says anything about automatically winning, chuckle condescendingly and tell him it's a common misconception. Don't be afraid to engage him in a brawl.

Sometimes you run across somebody who thinks the eight-ball is neutral, meaning that it can be used as the first object ball in a combination shot. Bollocks. That's a foul.

Another peculiar thing you sometimes run across is somebody who thinks that illegally sunk balls have to come out and get put back on the table somewhere (assuming it's not a coin-operated table and such a thing is even possible). In such cases it is advisable to perform some sort of mocking monkey dance. If, despite this effort, he actually places a ball back on the table, you may jump onto the table and deftly kick the ball towards him, yelling "goooooal!"

Here is an excellent rule to know: If, on your eight-ball shot, you sink the cue ball and the eight-ball doesn't go in -- you don't lose! That's right. The game continues. This rule is not commonly known. The common house rule is that you lose. Because the event is a fairly common one, it is advisable to keep a crumpled copy of the official rules in your back pocket just in case. Our advice to you is to keep mum and accept the win if it happens to your opponent, but if it happens to you, whip out the rules with one hand and use your other hand to grab a beer bottle and smash it against the bar.

This is another of our original contributions to the game of pocket billiards. Well, go ahead: Call it sexist. We'll have you know we despise all forms of piggish discrimination, but still it's nice to hold a door for someone now and then isn't it? And we heartily agree that a woman can be just as good as any man at the game of pocket billiards, and indeed we have been soundly thrashed by many women players in our time. But let's talk about ordinary reality among players who are still very much beginners. If a woman sinks something that isn't strictly intended, will a gentleman prevent her from continuing to shoot if she wants to? And if she misses everything completely, will a gentleman prevent her from re-spotting the cue ball and trying again? We say no. She may decline the advantage, and that is her prerogative. But Lasses' Rules means don't be so strict; be chivalrous. And why shouldn't men, under similar circumstances, be given the same consideration, you may ask? Well, we're not stopping you. If you're a man and you want to invoke Lasses' Rules, go right ahead. We'll try not to snicker.

Again, this is a John and Abby original. If there is an annoying bunch of balls all packed together, for example after a bad break, well, you might consider it part of the challenge of the game to pick shots off the edges until the pack loosens up a bit. Indeed, this situation is one of the integral challenges of the game of straight pool. On the other hand, in eight-ball it is nothing more than an ordinary pain in the ass. Under the Public Service Rule, a player can just smash them up, as a public service, without worrying about calling any shots. Any of his or her balls that go down count as fully legitimate, and the player continuesĖ?like a second break shot, if you will. One should of course call "public service" in advance, and the cluster should include both stripes and solids.

All right, there you have them: The perfect set of rules for eight-ball. Remember, when in doubt about the rules or what to do against an intimidating opponent, there is always the option of going "helter skelter." In other words, it is fully consistent with old-school billiards etiquette to invoke generalized confusion and violence. These days, with the proliferation of upscale yuppie pool halls, the image of the game has been cleaned up considerably, and such antics are generally frowned upon. This antiseptic new trend has done much to enhance the popularity and safety of the game and we commend it heartily, for it renders most opponents completely unsuspecting and highly vulnerable to the time-honored dirty tactics of yore. Thus one will want to develop a working familiarity with some essential concepts of pool hall violence.

First, it is a common instinct to grab a pool cue in a confrontational situation; however, if it comes down to that, the weapons you really want are the balls. They are extremely hard, there are many of them, and they can be launched from a distance.

Second, be aware of your environment. Know the location of useful objects such as barstools and full drinks, and keep a clear path to the nearest exit.

Third, use distractions. One of the best things to have in this regard is a copy of the official rules of the game, or some crumpled paper that can be alleged to be the official rules of the game. In the heat of a dispute over procedures, one can then whip the document out of one's pocket, shout "read the rules" while hurling them in the direction of the opponent's face, and create the momentary confusion that is so essential to reaching the exit before one is caught and pummeled out of recognizable shape.

Study these words well, and internalize the concepts; you will be well on your way to awakening your inner pool shark.